History

St Anne’s Limehouse is one of Nicholas Hawkmoor’s six great East London churches. The foundations were laid out in open fields in 1712 during the reign of Queen Anne, who taxed coal barges passing on the Thames to pay for it. The church was Hawksmoor’s first solo design and displays several typical aspects of his Baroque style – its monumental size, the contrasts of light and shade, the oversized classical elements and the eclectic creativity of its tower.

Characteristically, Hawksmoor made several design revisions during the construction of St Anne’s, and the mysterious pyramid in the churchyard may be a by-product of his earlier proposal for the towers at the east end. The steeple was built in 1718-19, with the church furnished between 1723 and 1725, and consecrated in 1730. Its western tower displays the Royal Navy’s White Ensign and is visually dominant from the River Thames. St Anne’s Limehouse became a landmark for every ship entering the Pool of London.

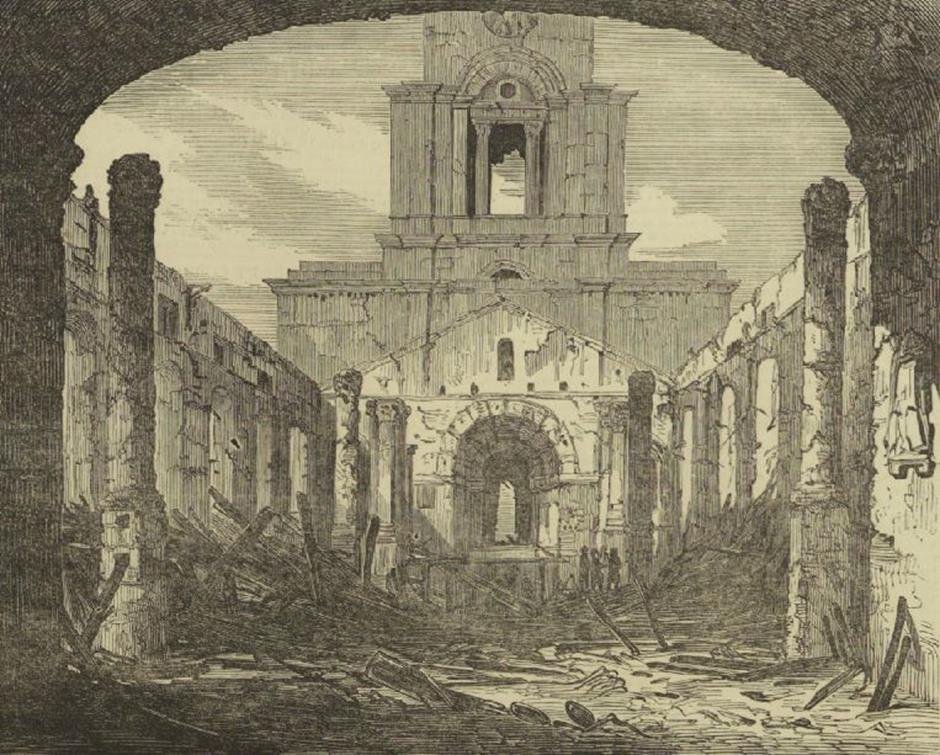

Attitudes to Hawksmoor’s powerful architecture were put to the test in the high Victorian era. St Anne’s was gutted by fire on Good Friday, 1850. Philip Hardwick, one of the leading Victorian classicists of the day, led the sensitive restoration of Hawksmoor’s masterpiece. He also commissioned the famous stained glass artist Charles Clutterbuck to create the Great East Window. The original eighteenth-century organ by Richard Bridge of Holborn (1741) was lost in the fire and replaced with The Grand Organ, purchased from the Great Exhibition of 1851 for just £800.

There followed more than a century of neglect, but eventually steps were taken to rescue Hawksmoor’s masterpiece. St Anne’s Church Conservation Area was created in July 1969. Care for St Anne’s was launched in 1978. In 1980, repairs to the external walls of the nave began, under the architectural direction of Julian Harrap. Bodies were removed from the vaults at the east end of the crypt to provide a meeting room, kitchen and toilets. In the second phase, Harrap strengthened the roof, adding a supplementary structure of tubular steel trusses to sit alongside the deteriorating Victorian trusses put in by Philip Hardwick after the 1850 fire. The third phase restored the great tower, the massive 1839 clock by John Moore & Sons of Clerkenwell, and rebuilt the churchyard wall, gates and railings. In 2002, Bill Drake of Buckfast, Devon, restored the Victorian organ.

-

In 1711, an Act of Parliament in England set up the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches to serve new parishes in the fast-growing suburbs of London. The work was funded from a tax on coal imported into the city. Although this ambitious target was not achieved, twelve churches were built and one of these was St Anne’s Church Limehouse.

-

Queen Anne decreed that as the new church was close to the river it would be a convenient place of registry for sea captains to register important events taking place at sea. Therefore, she gave St Anne's Church the right to display the second most senior ensign of the Royal Navy, the White Ensign. The prominent tower with its golden ball on the flagpole became a Trinity House ‘sea mark’ on navigational charts, and the Queen's Regulations still permit St Anne's Limehouse to display the White Ensign 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Due to the perilous climb to the top of the tower, St Anne’s White Ensign is refreshed just two to three times a year. “I return the old flag to HMS President [the Royal Navy’s reserve building, near St Katherine’s Dock] and exchange it for a fresh one,” says Darren Macleod. “Richard (Bray, the rector) likes to have a clean flag for Remembrance Sunday,” adds Gus Collin.

-

The architect Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736) began work as Sir Christopher Wren’s assistant from 1684, contributing to the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral and more than fifty parish churches destroyed in London’s Great Fire of 1666.

The early eighteenth century was a time of intense interest in early church history. St Anne’s limited adornment and oversized classical elements express a Doric order, revealing Hawksmoor’s awareness of Roman and Byzantine precedents, reimagined in his grand Baroque style.

Further examples are the church’s detached position within a sacred enclosure, its generous allocation of space to porches, narthex and preparatory rooms at the west end, and its two vestries at the east.

The church’s unusually precise orientation (only 1° from true East) probably reflects the influence of the scientist Edmund Halley, who was a member of the commissioning body at exactly the same time as he was developing a declination-corrected magnetic compass.

-

Remarkably, a churchwarden named Joseph Adams had taken out an insurance policy only three months previously, and the Rector and parish council had no hesitation in restoring what had been lost. Their architect, Philip Hardwick, reinstated the burnt-out roof using the same modern structure as Euston’s Great Hall, but the visible plasterwork of the ceiling was a restoration of Hawksmoor’s original. Joinery destroyed in the fire was carefully replaced. Its excellent detailing breathes the spirit as well as the appearance of eighteenth century woodwork.

-

Philip Charles Hardwick (1822–1892) was born in Westminster in London, the son of the architect Philip Hardwick (1792–1870) and grandson of architect Thomas Hardwick (junior) (1752–1825). His mother was also from an eminent architectural family, the Shaws.

Hardwick exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy between 1848 and 1854. He worked in the City of London, where he became the leading architect of grandiose banking offices, mainly in an Italianate manner. He designed five City banks, including Drummond's in Trafalgar Square (1879–81), and was architect to the Bank of England from 1855 to 1883. His best known work was the Great Hall of London's Euston railway station (opened on 27 May 1849).

-

Sir Arthur Blomfield (1829-1899) was Hardwick’s pupil. In 1856, he designed the new oak pulpit. Unusually for the time, Blomfield’s distinguished career was characterised by a high degree of respect for preservation of historic fabric. Perhaps he learned those values at St Anne’s.

-

The new Grand Organ was a three-manual display instrument built by Messrs Gray and Davison expressly for the Great Exhibition of 1851. From May to October of that year, its thrilling tones had filled the vast interior of Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace in Hyde Park. Once the Exhibition closed it needed a new home. The churchwardens were looking for a replacement just at the moment when the display instruments from the Great Exhibition of 1851 were being dismantled for the relocation of the Crystal Palace from Hyde Park to Sydenham. The Grand Organ had been awarded a gold medal by a jury that included the composer Hector Berlioz. Magnificently powerful and thrilling in tone, it was perfectly suited to the architectural setting of St Anne’s. Little altered over the course of the twentieth century, it was beautifully restored in 2002 by Bill Drake of Buckfast, Devon, with a grant from the Pilgrim Trust.

-

St Anne's huge crypt was used as a bomb shelter during the blitz, from 1940 to 1942. Remarkably, the church escaped significant structural damage. However, the nearby bomb blasts of two world wars have distorted all the panels of the Clutterbuck window.

-

The most remarkable aspect of the second phase of Harrap’s restoration was hidden from view up in the void above the elaborate plaster ceiling of the nave. After the disastrous fire of 1850, Philip Hardwick had installed a timber and cast iron structure similar to his design for the Great Hall of Euston Station. Over time the timber ribs were beginning to slip from their cast iron shoes, impairing the roof’s load-bearing ability. Harrap’s elegant solution was to employ a modern technology of tubular steel trusses and ties in a supplementary structure sitting alongside the Victorian trusses, ready to take the strain in case of deflection.

-

When the great tower was restored, a meticulous stone-by-stone survey was carried out which won for St Anne’s and Julian Harrap Architects the inaugural John Betjeman Memorial Award for Conservative Repair of Churches and Chapels of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, SPAB.